A short series of notes for myself as I learn more about the AI ecosystem as of September 2025. The driver for all this is understanding more about Apache Flink’s Flink Agents project, and Confluent’s Streaming Agents.

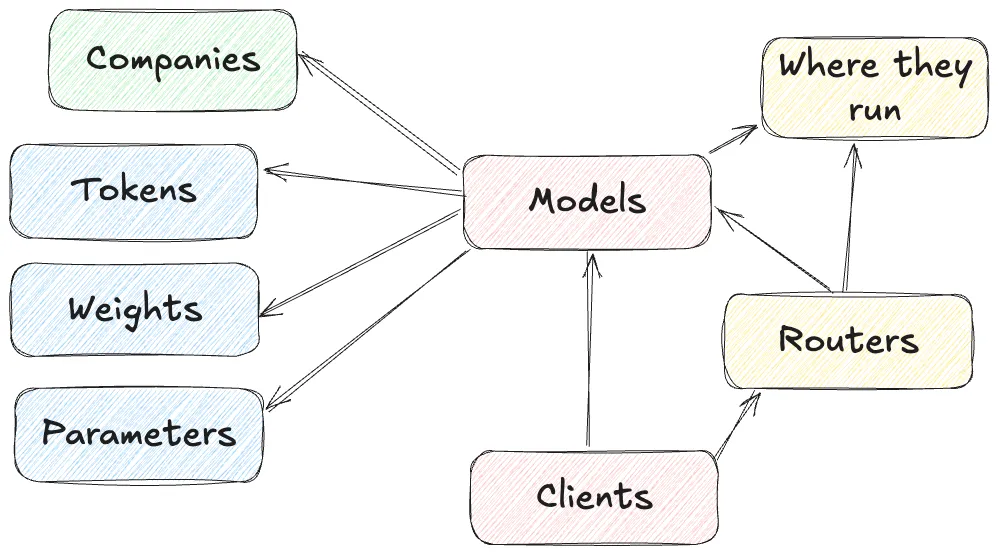

Having poked around MCP and got a broad idea of what it is, I want to next look at Models. What used to be as simple as "I used AI" actually boils down into several discrete areas, particularly when one starts looking at using LLMs beyond writing a rap about Apache Kafka in the style of Monty Python and using it to build agents (like the Flink Agents that prompted this exploration in the first place).

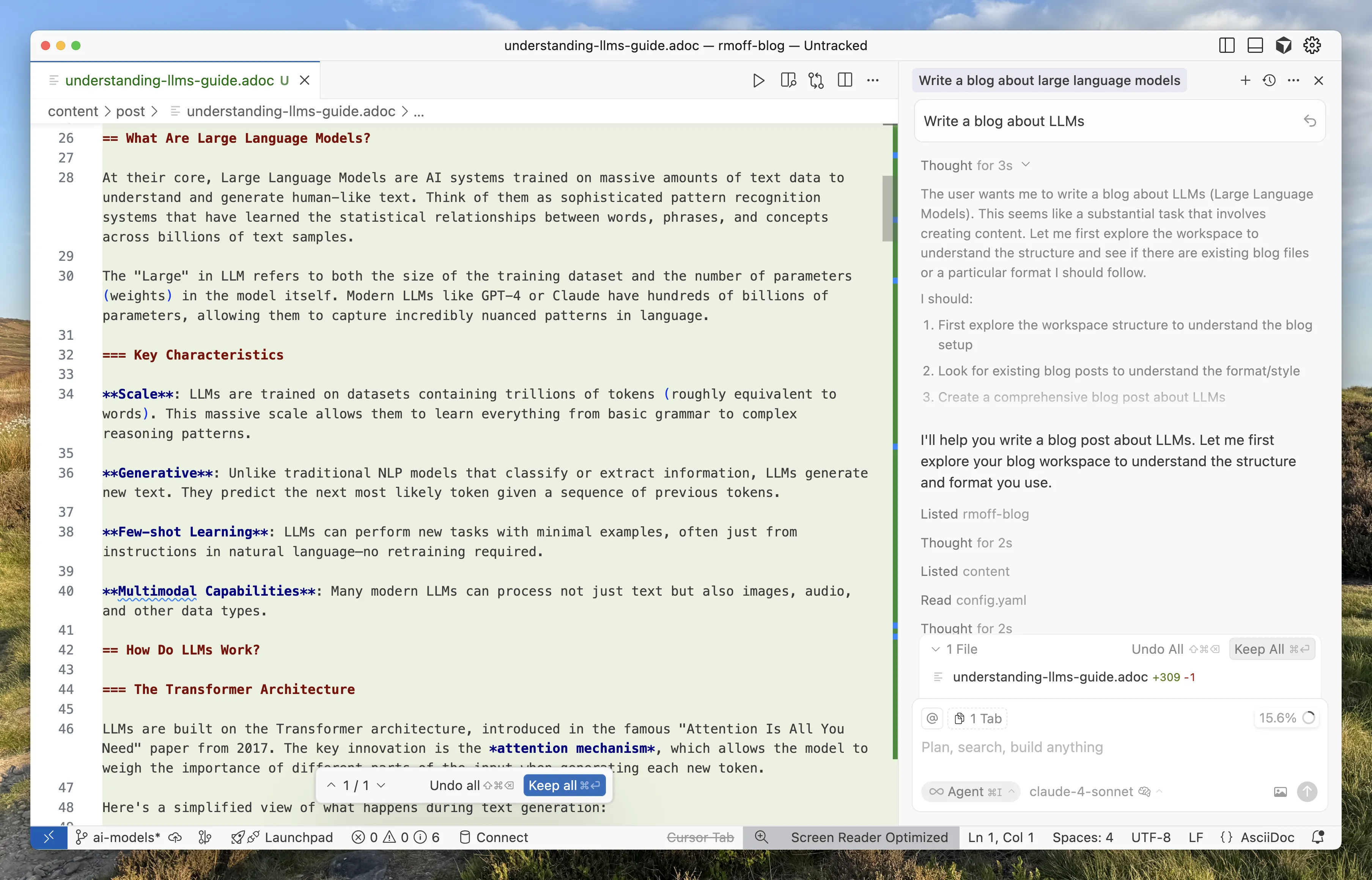

Models (Large Language ones, to be precise) 🔗

This is the what it’s all about right here. Large Language Models (LLMs) are what piqued the interest of nerds outside the academic community in 2023 and the broader public a year or so later. What used to be a "OMFG have you seen this" moment is now somewhat passé. Of course I can ask my computer to write my homework assignment for me. Of course I can use my phone to explain the nuances of the leg-before-wicket rule in Cricket.

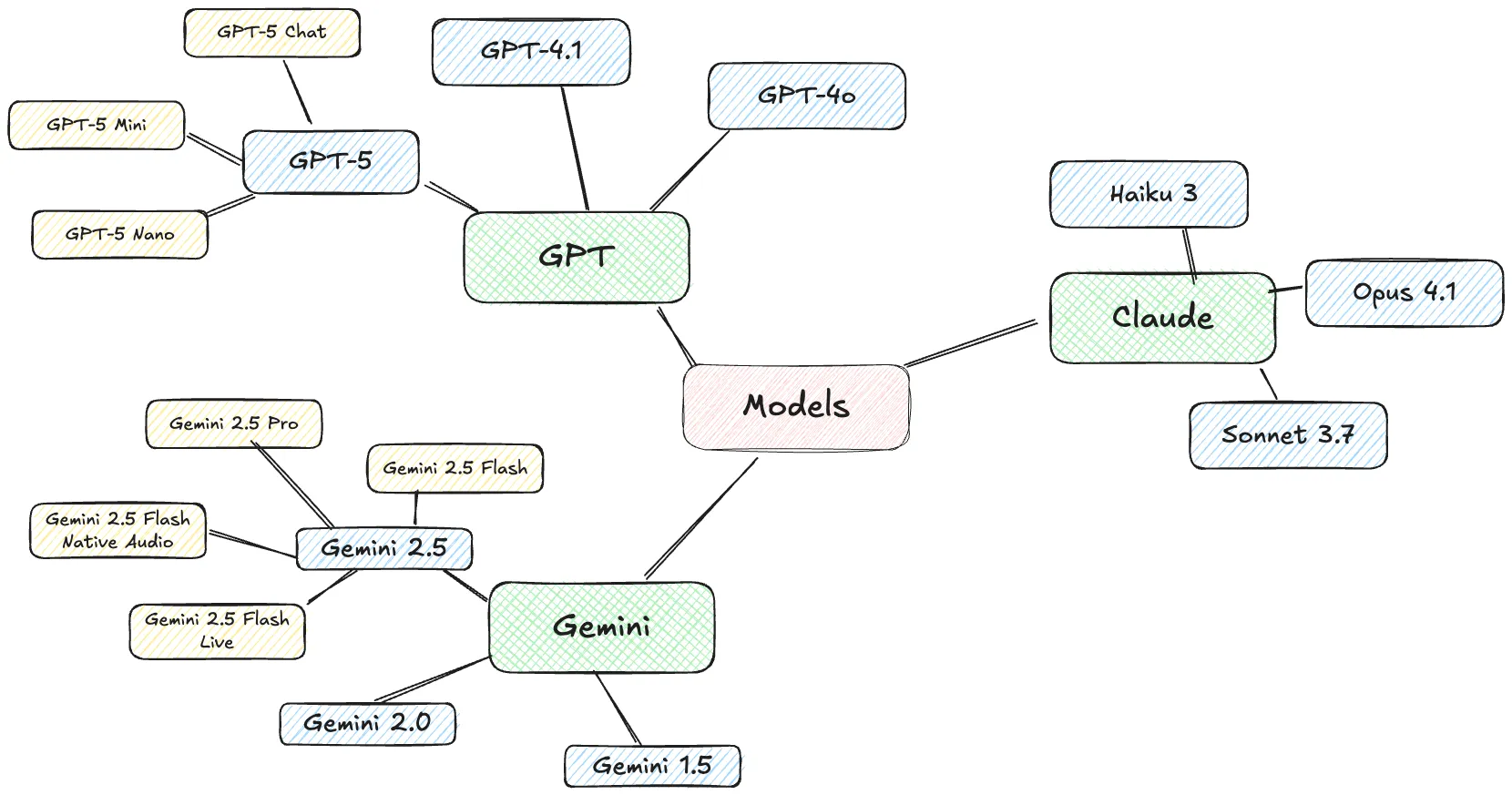

Without a model, the whole AI sandcastle collapses. There are many dozens of LLMs. The most well-known ones are grouped into families and include GPT, Claude, and Gemini. Within these there are different models, such as GPT-5, Claude 4.1, and so on. Often these models themselves have variants, specific to certain tasks like writing software code, generating images, or understanding audio.

Companies 🔗

The big companies behind the models include:

-

OpenAI (GPT)

-

Anthropic (Claude)

-

Google (Gemini)

-

Meta (Llama)

How does it work? 🔗

Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.

Srsly tho, I’m not going to even pretend to try and understand how LLMs works. Just as I couldn’t tell you how the CPU in my laptop works, but I know that it’s there and waves hands does stuff, the same is true for LLMs.

You give them text, they give you a response.

If you want a really good overview of LLMs, have a look at this excellent talk from one of the OGs in the LLM space, Andrej Karpathy:

Hallucinations 🔗

One of my favourite descriptions of LLMs likened them to an over-eager, hungover, intern. They can do a lot, and know a lot of the words, but you’d never quite trust what they write.

As LLMs improve, it’s less likely you’ll get completely BS responses from them, but part of the risk is that they usually express themselves extremely confidently. Here’s what an LLM told me about my home town:

Ilkley:

Known for its stunning lakes (Lythwaite Lake) and the Dung scale viaduct, which provides a breathtaking view of the surrounding landscape.

Has a rich history, including being part of the Lancashire cotton industry in the 1800s.

Sounds plausible, right?

But Lythwaite Lake and Dung scale viaduct do not exist (nor is there a lake or viaduct near the town).

And worse, Ilkley is very much in Yorkshire, not Lancashire!

Of course, it’s easy to cherry-pick these examples. If I ask a better model about Ilkley, it is completely right:

Ilkley:

Known for its dramatic moorland (Ilkley Moor) and the Cow and Calf rocks, offering sweeping views over Wharfedale and inspiring the song “On Ilkla Moor Baht ’at.”

Has a rich history, from its Roman fort (Olicana) and medieval origins to becoming a Victorian spa town famed for hydrotherapy and elegant architecture.

Tokens 🔗

The input and output of LLMs is measured—and in many cases, charged—on the basis of tokens.

|

Just like the video above explaining how LLMs work, if you want to know about details of tokenisation check out this explainer: |

In some cases, the number of words is equivalent to the number of tokens:

$ ttok never gonna give you up

5but often not:

$ ttok apache flink

3

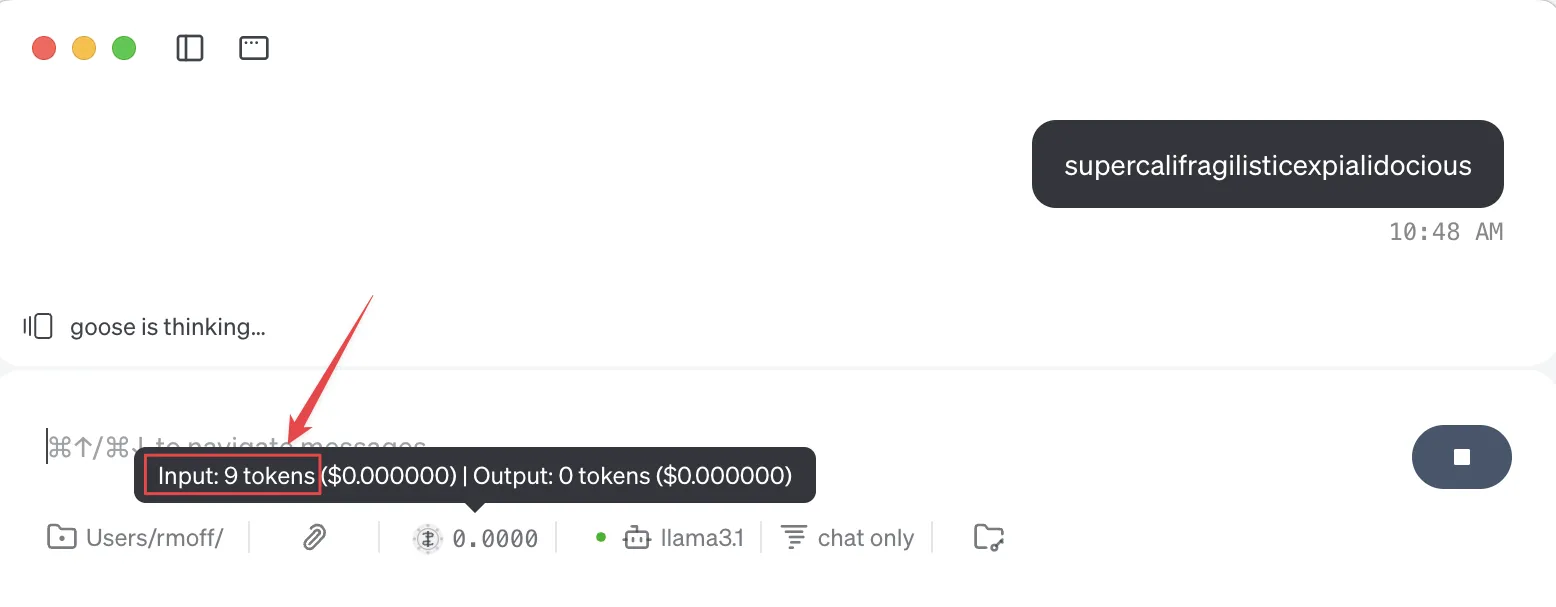

$ ttok supercalifragilisticexpialidocious

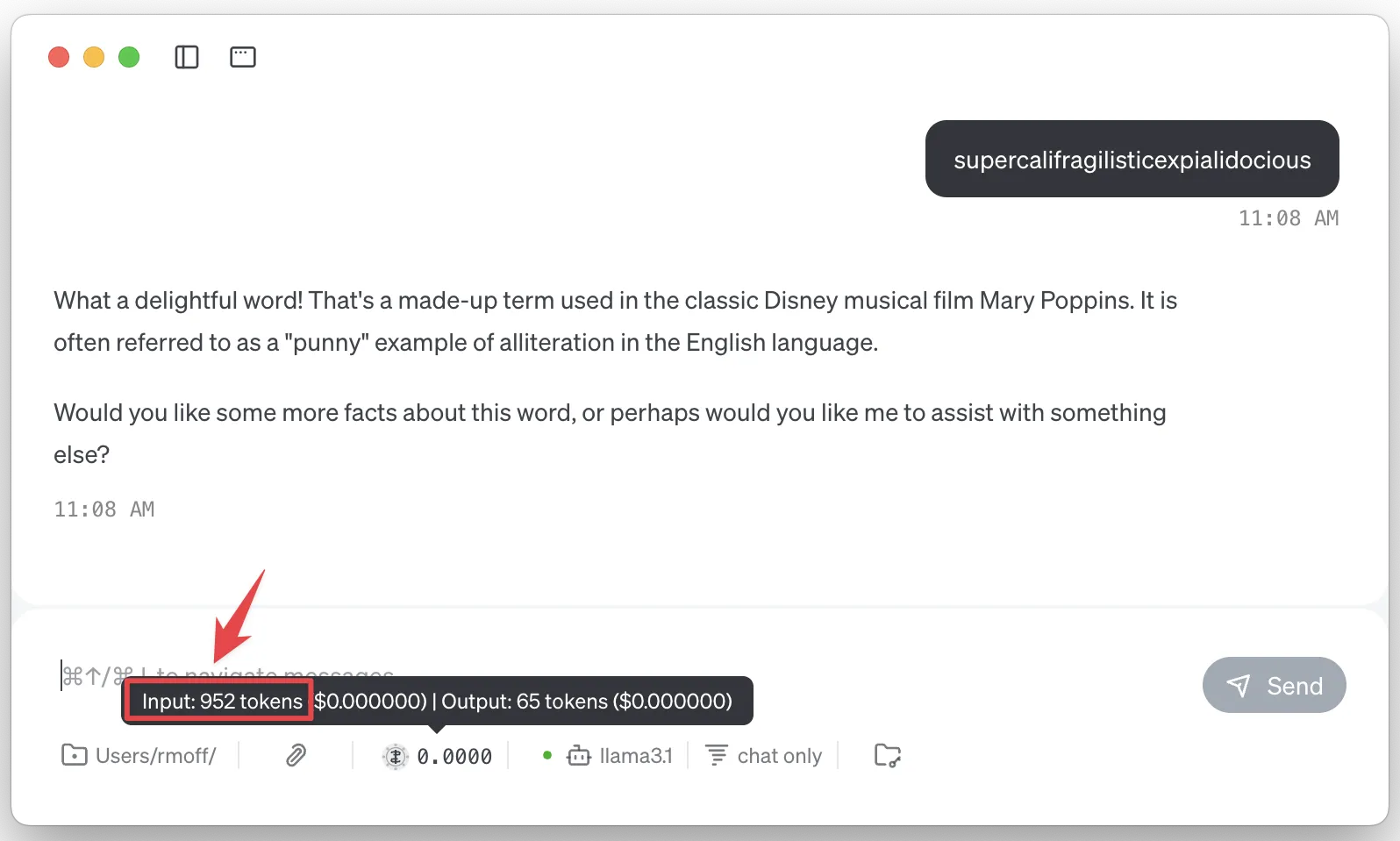

11Different LLMs may use different tokenisation too. You can use the ttok tool (shown above) to explore tokenisation in more detail. Some tools, such as Goose, will also show you how many tokens are used:

You’ll notice that as well as the token count, there’s a dollar amount next to it. Since I’m running the model locally (using Ollama) there’s no direct cost for the invocation of it. Where the token count matters is when you’re using remote models, like GPT or Claude. These are charged based on the number of tokens used, often listed as a cost per 1M tokens.

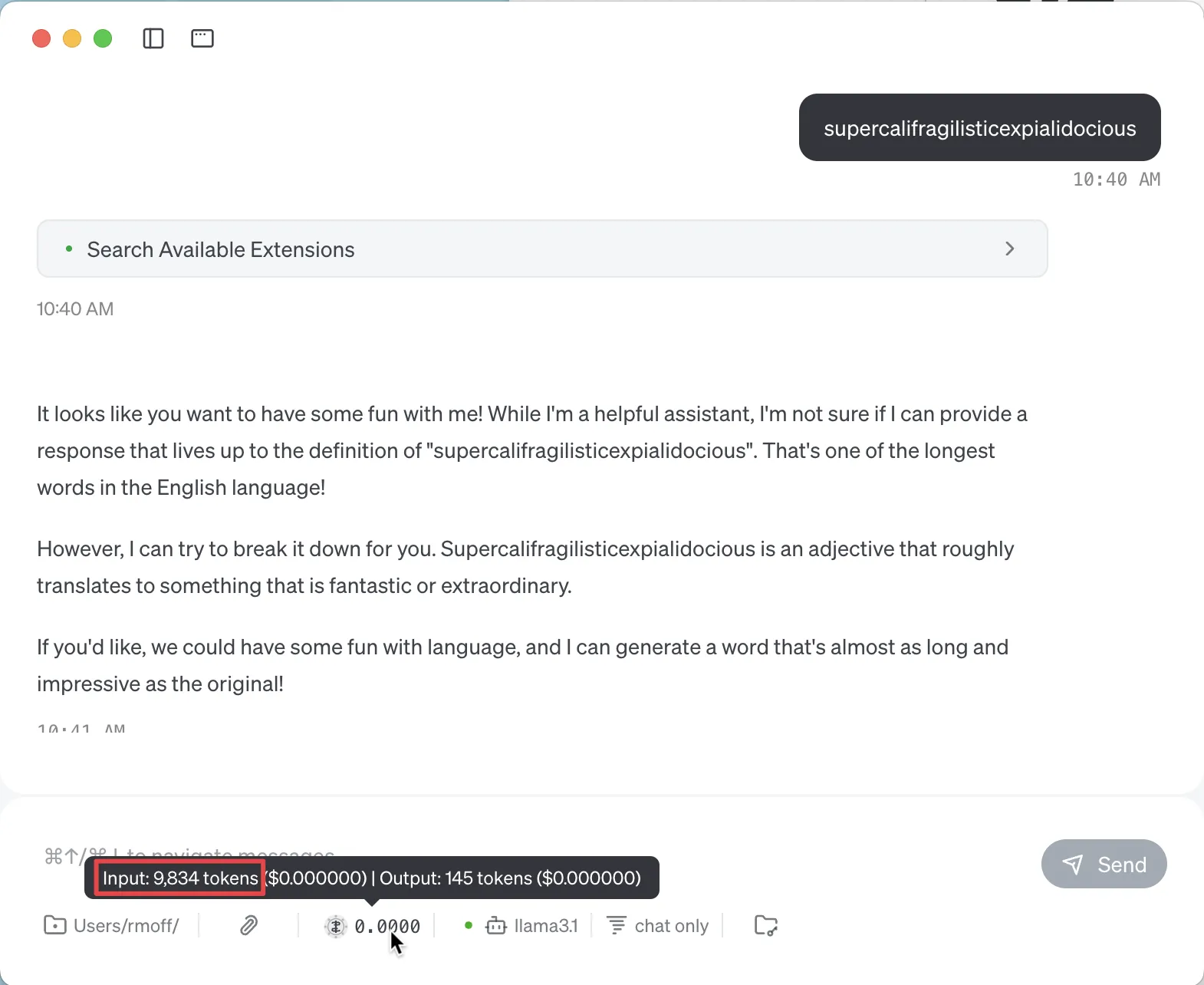

Nine tokens might seem like a drop in the ocean of a million, but look at this:

The same input prompt (supercalifragilisticexpialidocious) but somehow I just used nearly 10k tokens!

If you read my blog post about MCP you’ll know that LLMs can make use of MCP servers (often generically referred to as "tools" or "extensions").

They can be used to look up further information to support the user’s request ("what films have they rated the highest"), or even invoke actions ("book two tickets at the local cinema to see Top Gun on Monday at 8pm").

So when I gave the agent the prompt supercalifragilisticexpialidocious, what it actually did was include information about all of the tools configured, so that the LLM could choose to use them or not—and this took up a lot of tokens, because there were several tools configured.

So if I disable the tools/MCP servers, the token count should be back to just that of the input expression?

Not so. And that’s because most of the time you use an LLM you’re doing so with a particular purpose or framing, and so a system prompt will help focus it on what you want it to do.

For example, here is the same input, but with two different system prompts.

$ echo "Internet" | \ (1)

llm -m gpt-oss:latest \

-s "Define this word. Be concise." (2)

**Internet** – a global network of interconnected computers that exchange data using standardized protocols, enabling communication, information sharing, and services across the world.

$ echo "Internet" | \ (1)

llm -m gpt-oss:latest \

-s "Define this word to a five year old. Be concise." (2)

The internet is like a giant invisible playground for computers. It lets them share pictures, videos, games, and messages so you can learn, play, and talk to friends from anywhere.| 1 | User input |

| 2 | System prompt |

Ultimately the system prompt is just a bunch of tokens that get passed to the LLM; and that’s probably what we’re seeing in the screenshot above where the token count is higher than that of the input text alone.

Why does this matter? 🔗

Because someone has to pay for all this fun, and how many tokens you use determines how much you’ll pay. You might be using the LLM provider’s API directly and thus directly exposed to the token cost, or you might be using a tool whose authoring company pays the API bills and in turn will cap your invocation through the tool at a certain point. You might think a million tokens sounds a lot, but this can easily get burnt through with things like: * MCP usage, in which the output from an API call might be a long JSON document - and often multiple API calls will get strung together to satisfy a single user request * Coding help, when the LLM will have to be given reams of code across potentially many files

Context Window 🔗

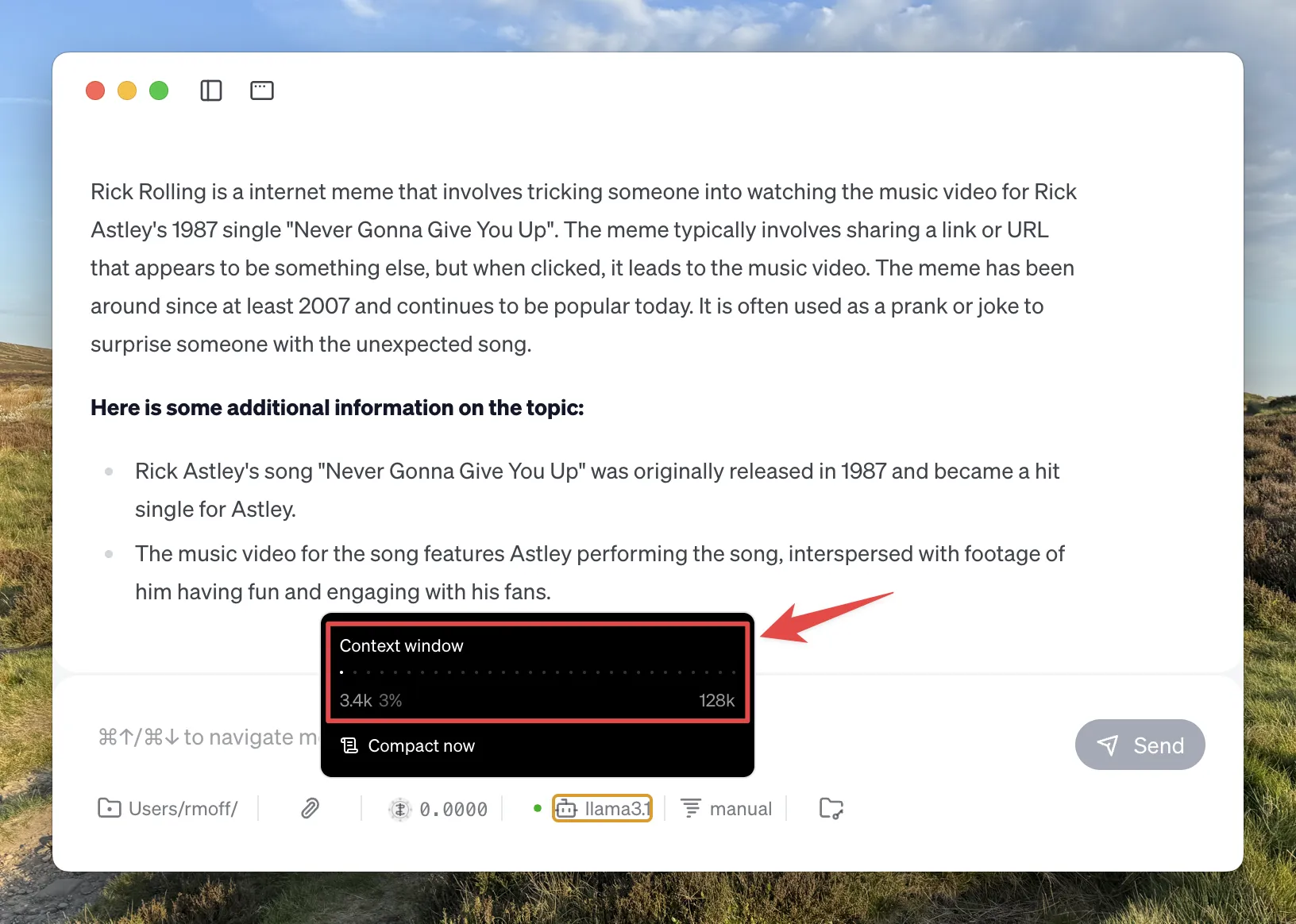

When you interact with an LLM, it can 'remember' what you’ve told it—and what it’s told you—before. This is called the context window, and is measured in tokens.

Generally, the smaller the context window the faster a model will return, compared to a larger window. Once the window is full you’ll see the model start to "forget" things, or just refuse to run.

Some AI tools will expose the current context window size, like Goose:

You can also sometimes 'compact' the context window, which will in effect summarise everything "discussed" so far with the LLM and start a new conversation. Since the summary will be shorter than the dialogue from which it was created, the context window will be smaller.

Weights & Parameters 🔗

After many years working with open source software, I was puzzled by the new terminology that I started to hear in relation to LLMs: "Open Weight".

In terms of software alone, open source has a strict set of definitions, but one of the key ones from an end-user point of view is that I can access all the source code and in theory could build the program from scratch myself.

When it comes to LLMs it’s not quite so straightforward. Watching Andrej Karpathy’s video I’ve picked up the basic understanding that you’ve got the mega-expensive pre-training in which vast swathes of the internet and beyond are boiled down into a model. He gives the example of Llama 2 costing $2M and taking 12 days to train. The size of the model is defined by the number of parameters. Broadly, the greater the number of parameters, the greater the accuracy of the LLM. Fewer parameters means less computing power needed and potentially less accurate results—but depending on what you’re asking the LLM to do can sometimes be a good tradeoff.

Out of this pre-training is then a core model which is then trained further in what’s known as fine-tuning. This is cheaper, and faster, to do. It can be used to specialise the model towards particular tasks or domains.

Companies approach the sharing of models in different ways. Some keep absolutely everything to themselves, giving the end user simply an API endpoint or web page with which to interact with the model that they’ve built. Others will perhaps share the pre-trained model (but not the source data or code that went into training it), giving people the opportunity to then train it further with their own fine-tuning. This is the "Open Weight" approach.

You can read more about Llama 4 and Llama 3 on the Meta AI blog, as well as GPT-OSS from OpenAI. This post on Reddit is also interesting: The Paradox of Open Weights, but Closed Source

Clients 🔗

OK, so we’ve got our models. They come in different shapes and sizes, and some are better than others.

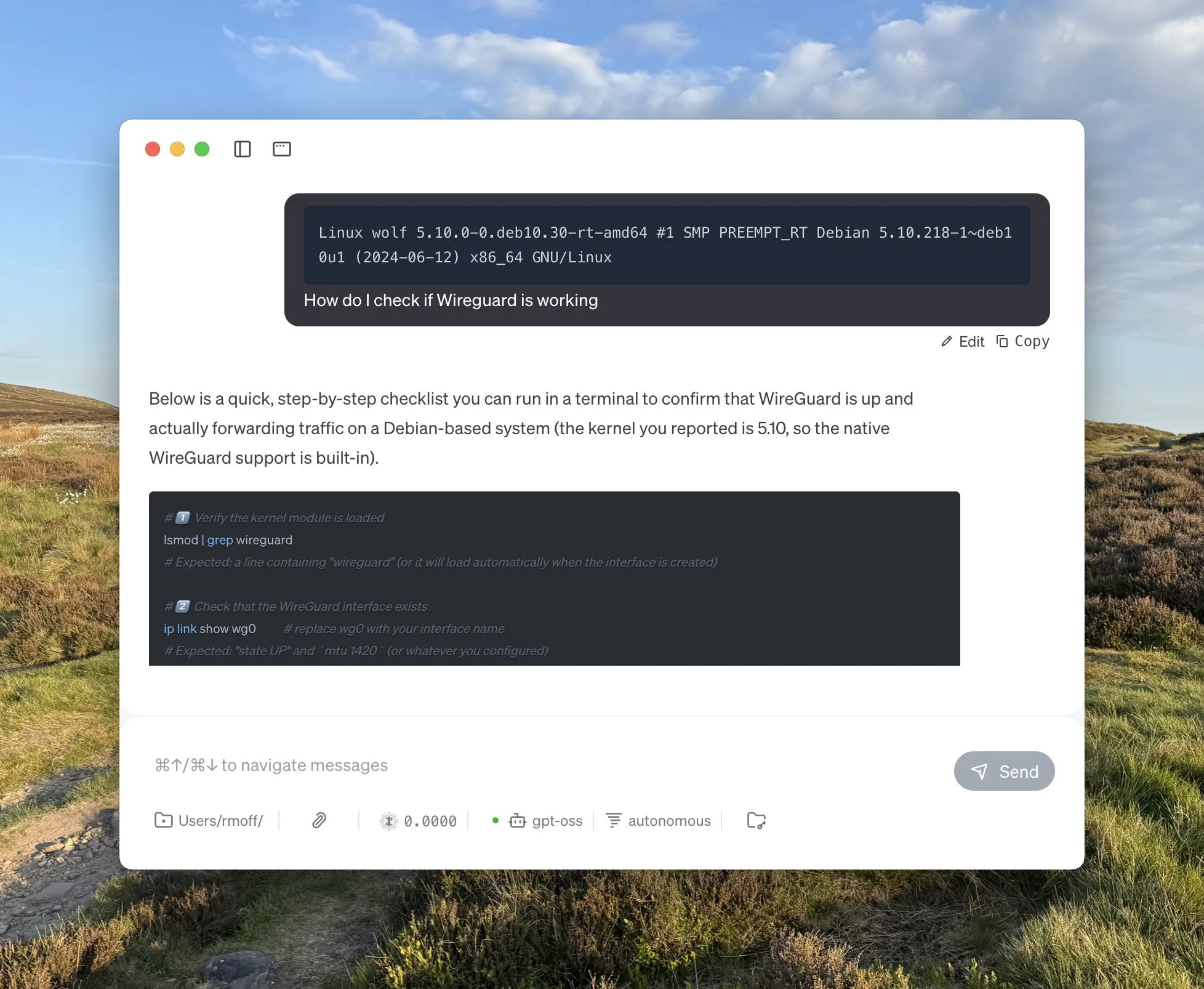

To use an LLM, one needs a client. Clients take various forms:

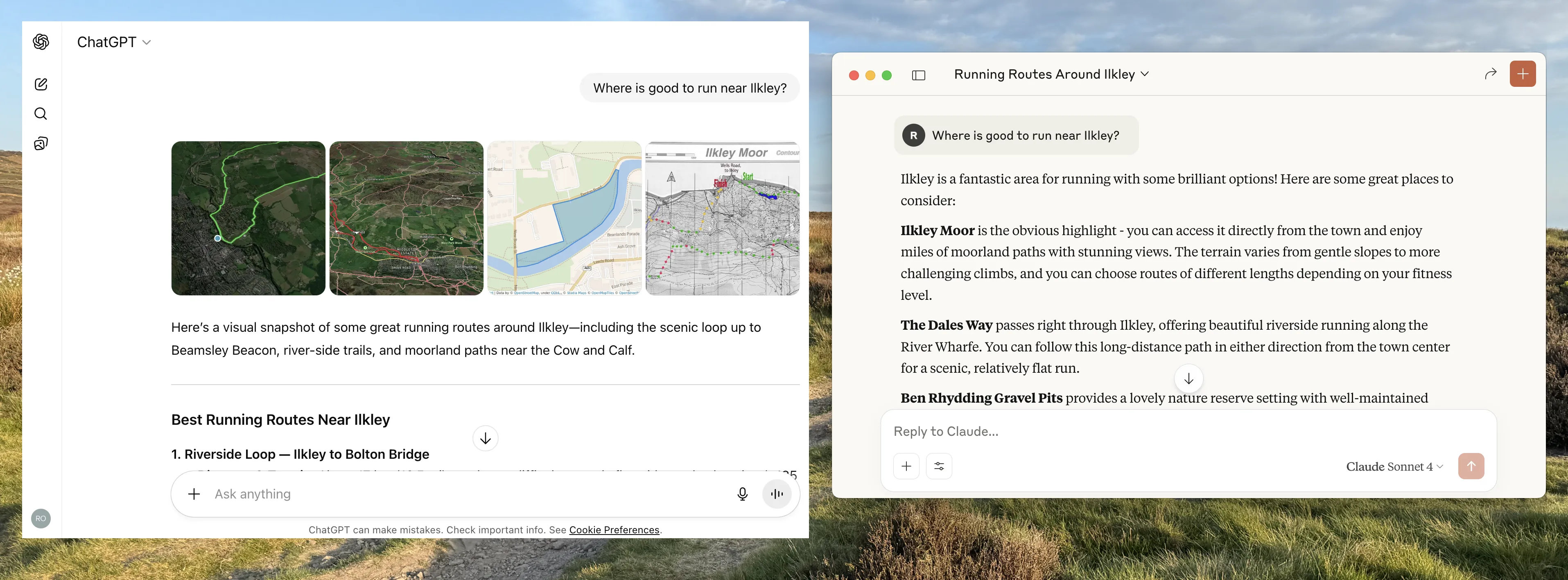

-

Desktop and Web clients, specific to the AI company developing a family of LLMs. These include ChatGPT and Claude.

-

Tools built around AI functionality (e.g. Cursor) or with it bolted on whether you want it or not (i.e. every bloody application out there these days 😜). Some of these will give you access to a set of models, whilst others will mask the model itself and just call it

"magic""AI"

-

Model-agnostic interfaces, including:

-

Raycast, which as part of its application gives the user the option to interact with dozens of different LLMs

-

Simon Willison’s

llmCLI:# Use GPT-OSS model $ llm -m gpt-oss:latest 'What year was the world wide web invented? Be concise' 1989. # Use Llama 3.1 model $ llm -m llama3.1:latest 'What year was the world wide web invented? Be concise' The World Wide Web (WWW) was invented in 1989 by Tim Berners-Lee. -

Goose, which is an an extensible open source AI agent. I’ve not used it a ton yet but at first glance it at least gives you a UI and CLI for interacting with LLMs and MCPs:

-

Where the model runs 🔗

Running LLMs takes some grunt, which is why they’re particularly well suited to being provided as hosted services since someone else can absorb the cost of provisioning the expensive hardware necessary to run them.

There are 3 broad options for getting access to running a model (assuming you’re using a client that has pluggable models; if you’re using something like ChatGPT then you just access the models through that alone and they run the models for you):

-

My cloud

-

My laptop, my on-premises servers with some big fat GPUs, etc

-

-

Their cloud

-

Someone else’s cloud

-

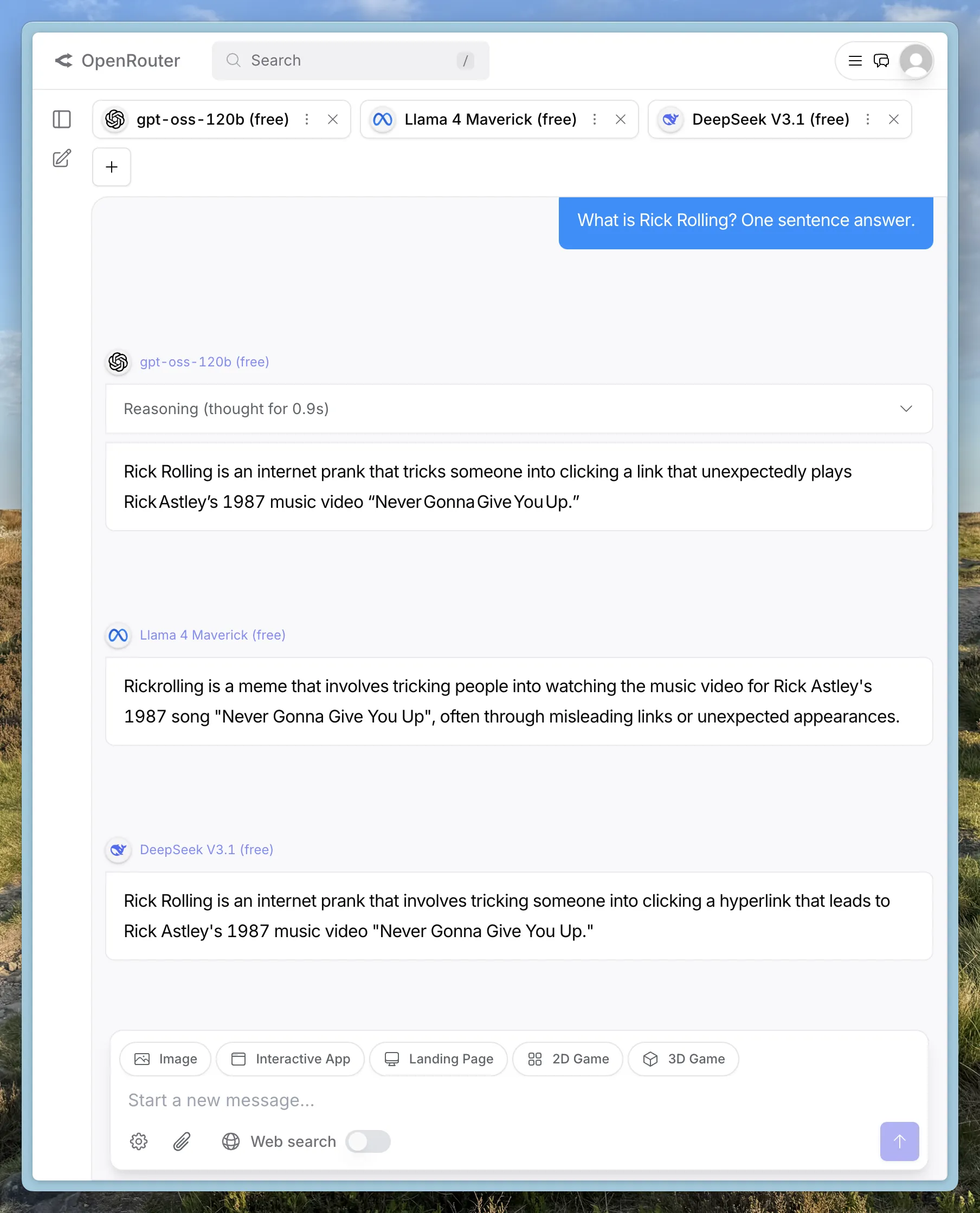

Models hosted by 3rd party providers, including Amazon Bedrock, Azure AI Foundry, OpenRouter, etc. The big providers like Azure and Amazon will usually have partnerships with some model companies and provide access to their models, whilst others may only offer access to publicly-available models (basically what you or I could run on our own locally, but with the necessary hardware behind it to perform well).

-

I’ve found OpenRouter particularly useful as it gives you access to free models, and the ability to run the same prompt across different models:

It also has a good catalog of models and details of which provider offers them.

Finally, OpenRouter is a pragmatic way to make use of the free models; gpt-oss:120b might sound nice and make claims about being as good as some of the closed-weights GPT models, but it’s irrelevant if it won’t run locally.

Routers 🔗

The final piece of the puzzle, for now, is routers.

Given that there are multiple models, and multiple places in which to run them, how do you decide which one to call? Different models are better at different tasks; or put another way, the big expensive models are usually good at everything but you may get a faster or cheaper (or perhaps even just more accurate) response from a specialised model. You could take the artisanal approach, and curate your model access based on your in-depth understanding of all models each time you want to call one.

Alternatively, you use a router, which is a model itself and one that is specialised in understanding LLMs strengths, analysing the type of workload you want to run, and routing it to the most suitable one.

Some routers include:

-

OpenRouter’s AutoRouter

You don’t have to use a router, but you’ll possibly see mention of them which is why I’m mentioning them here.

Also, because I got confused by OpenRouter also being a service provider, not just a router :)

|

Addendum: There are Models, and then there are Models (a.k.a. not all Models are LLMs) 🔗

As I wrote the third part in this little voyage of discovery I realised that my understanding of models—as I wrote about them in this article—was incomplete.

There are different types of model, and there are different purposes to which a model is put.

LLMs as I’ve discussed in this blog post are generative. They create (generate) new material based on their training over large datasets of text. There are other generative models that are not LLMs. These include those you might have also heard of like DALL-E and Midjourney, for generating images. There are also models for generating speech, music, and video.

Other models that aren’t generative do tasks such as:

-

Creating embeddings (as used in RAG)

-

Sentiment analysis

-

Anomaly detection

-

Forecasting and prediction

-

Analysing video, image, or audio, e.g.

-

Detecting objects

-

Transcribing speech

-

| Regardless of the type, what you call a model to get it to do something, it’s called inference. |