(This is an expanded version of the intro to an article I posted over on the Confluent blog. Here I get to be as verbose as I like ;))

My first job from university was building a datawarehouse for a retailer in the UK. Back then, it was writing COBOL jobs to load tables in DB2. We waited for all the shops to close and do their end of day system processing, and send their data back to the central mainframe. From there it was checked and loaded, and then reports generated on it. This was nearly twenty years ago as my greying beard will attest—and not a lot has changed in the large majority of reporting and analytics systems since then. COBOL is maybe less common, but what has remained constant is the batch-driven nature of processing. Sometimes batches are run more frequently, and get given fancy names like intra-day ETL or even micro-batching. But batch processing it is, and as such latency is built into our reporting by design. When we opt for batch processing we voluntarily inject delays into the availability of data to our end users. Much better is to build our systems around a streaming platform instead.

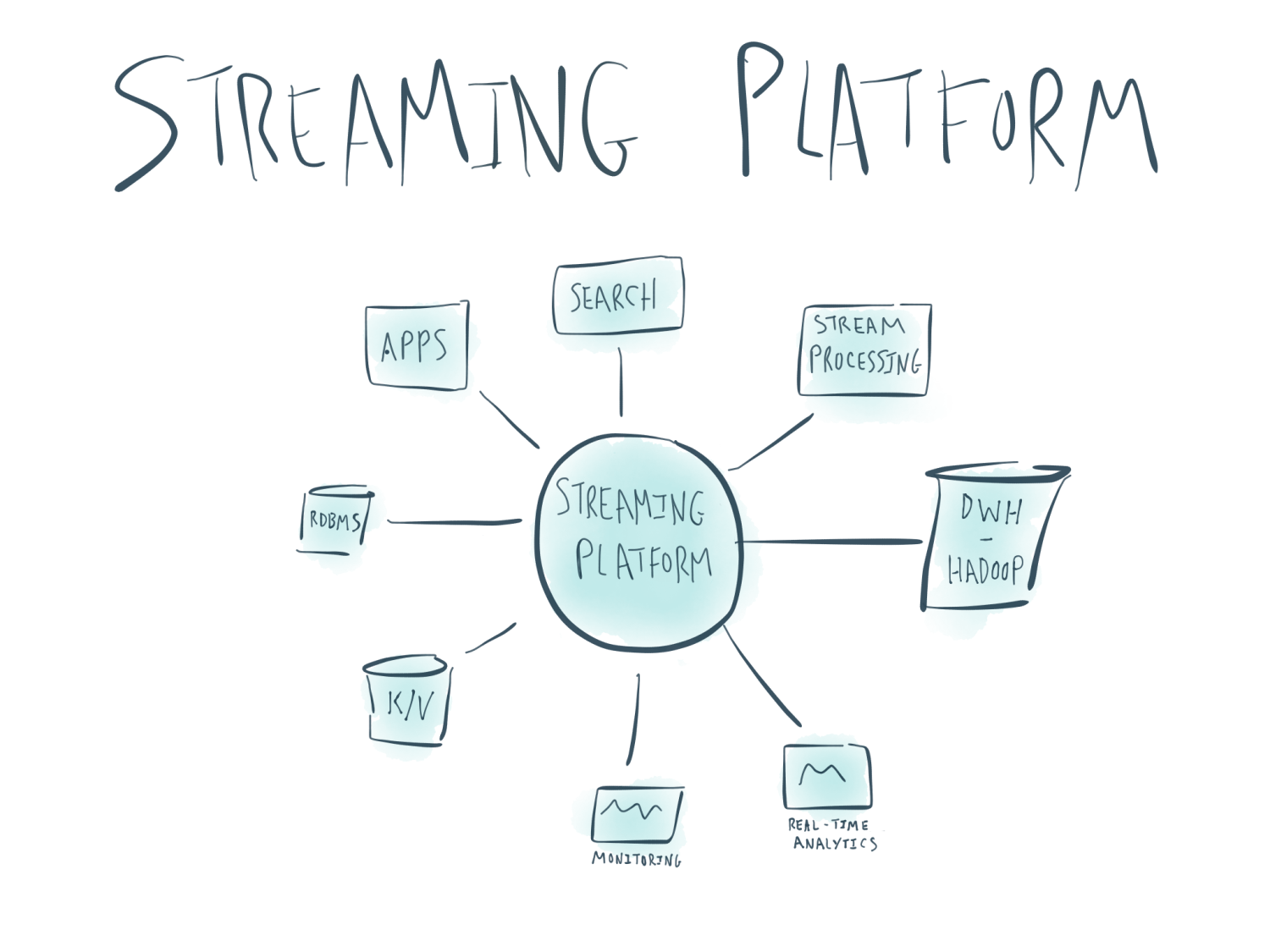

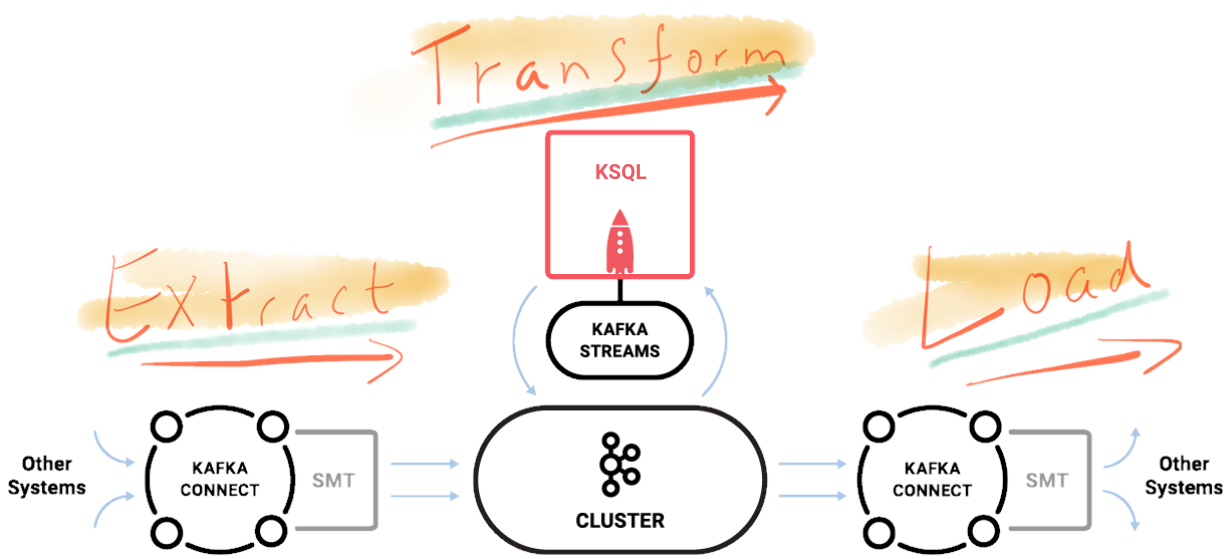

Apache Kafka is a distributed streaming platform, and as well as powering a large number of stream-based mission-critical systems around the world, it has a huge role to play in data integration too. Back in 2016 Neha Narkhede wrote that ETL Is Dead, Long Live Streams, and since then we’ve seen more and more companies moving to adopt Apache Kafka as the backbone of their architectures. Through Kafka’s Connect API pretty much any standard system can serve as the source of streaming data into Kafka. Once data is in Kafka, it is “just” a message; its source is irrelevant when it comes to how we want to use it. From within Kafka we can transform the data further, drive microservices, and stream the data out through Kafka’s Connect API to myriad targets. Which targets? Many targets!

- Often we’ll want to use the data not landed in a store, but as the input for event driven architectures that drive business processes.

- For long-term analytics we have the data lake concept, often hosted on technologies such as HDFS/Hive, S3/Athena, BigQuery, and Snowflake.

- Often we want refine elements of the data lake into what’s generally recognised as a data warehouse/mart for performance as well as formal modelling and audit of the data lineage. These may also reside on the same platforms as the data lake, or perhaps standard RDBMS such as Postgres, MySQL, Oracle etc.

- Real-time analytics can be served through slices of our events streamed to NoSQL stores such as Cassandra, or search-based tools such as Elasticsearch

- Elasticsearch and similar tools such as Solr are frequently used for search replicas/caches of data both to drive search in end-user applications and websites, as well as ad-hoc analytics and data exploration by analysts.

- More specific tasks often demand dedicated technologies, such as time series databases like InfluxDB, Graph analytics with Neo4j, and so on

As the above list demonstrates, how we think about data and what we want to do with it helps define the kind of technology we’re going to use to store it. A very important point to realise here is that you generally will not have just one target for your data. Kafka enables two vital architectural principles here:

- Stream your data from source into Kafka, and from there to target. Decouple your architecture to make it flexible and agile for future development. Resist the temptation to load it into your data lake first and then process it onwards. Why introduce completely unnecessary latencies and dependencies in your processing?

- Following on from the above, be aware that you can stream data from Kafka to multiple targets concurrently. If you want all your data in Hadoop for audit purposes, or just because it gives you a warm fuzzy feeling - you can do. But if you want to use that data somewhere else, you can stream it directly from Kafka. Perhaps you want to drive some alerting based on the events streaming in, or you just want the data in a second data store. Either way, you decouple that secondary use from Hadoop, making the pipeline simpler to maintain, less fragile—and without the latency!

From a point of view of data latency this first point above is critical. Getting data where you want it when you (and your users) want it is one of the key drivers of technology choice. Reducing the latency of data made available to users enables them to make more accurate business decisions. And if you don’t care about latency? Well that’s fine too; Kafka supports batch-concepts too, by virtue of the fact that it persists data which means that it is there for a consumer to read when the consumer wants to—even if that’s just as part of a once-a-day batch load.

As well as chosing the most appropriate technology for a particular task and being able to maintain a correct state of data in it via Kafka, using Kafka as our data backbone also lets us embrace and rationalise the proliferation of technologies in use across organisations as control moves away from central IT and out to individual business units. Instead of the futility of railing against this and trying to prevent it, with Kafka we can easily provide a feed of clean data to anyone who wants it, without impacting the design or availability of our central data architecture. Embrace the Anarchy!

Even if you don’t face the challenge of disparate systems and have a perfectly controlled and rational technology footprint, Kafka gives you the power to evolve this in a beautifully flexible manner. With Kafka at the heart of your architecture, you can replace sources without impacting downstream users of the data. You can add additional targets, or evaluate alternative technologies, alongside existing ones. All of this is done in a decoupled manner, enabling agile development of systems.

One last point for now is that in some cases, we don’t even want to store the data outside of Kafka. What is the nonsense, you may ask? Surely we must always land data to a database, to a data store? Not always. Here are two examples:

- Consider a source of data that you want to enrich and load to a target. Standard design would be to load the raw data into a database as the staging layer, and then enrich and transform it from there. Kafka itself is the staging layer here, acting as the central point for all inbound data.

- Kafka Streams has interactive query capabilities meaning that it can serve up the state of a stream (such as a point in time aggregation) directly from its local state store. Doing this, external applications can query a dedicated stream job to directly access data, without needing to land it at an intermediary data source. Interactive query generally fits operational systems better, such as realtime embedded dashboards, but where you do have these, challenge any assumptions that you have around the necessity of a database.

To read more about storing data in Kafka see Jay Krep’s recent article as well as an example of it in action at the New York Times.